The winter solstice seemed a perfect time to reflect on the past season and welcome bright new opportunities that accompany the returning sun. But clouds lay thick as doubt over South Australia’s coastline as my plane descended into Adelaide. Local news later reported it was among the area’s wettest days on record. Rain pounded so loudly on the roof of my rental car that I could barely hear the GPS directions.

“So much for a desert trip,” I muttered to the frantic windshield wipers. With my work assignment Down Under drawing to a rapid close, there was still one iconic biome I hadn’t experienced: the Outback. But I wanted something wilder than the standard Red Centre excursion, trapped at an overpriced resort offering segue tours around Uluru. Instead, I opted for the Flinders Ranges. Rugged red mountains, vast salt lakes…and, apparently, hydroplaning down the flooded A1. Not what I’d anticipated. Then again, if you’ve been following my blog for the past few years, you know that nothing about my life in Australia had gone as expected!

The downpour abated as I approached Lake Bumbunga. Tinged pink by a hardy species of algae, the salt lake spread an incongruous carpet of color amid the farmland. A sea-serpent sculpture made of old tires arched from the rosy water. I pulled off to stretch my legs and immediately started chasing a kestrel along the shoreline. When it spun me eastward, I gasped. Afternoon sun refracting through the drizzle painted a full rainbow across one end of the lake. I hadn’t seen one that stunning since Loch Ard Gorge in Victoria. Pagan sensibilities deep in my DNA took it as a good portent for my travels. What’s more, it turned the day into a miniature analogy of my Australian experience.

REFLECTION: Plunge into an alien world and persevere through a historic storm, even though you can barely see the road ahead. You may stumble into breathtaking wonders that make it all worthwhile.

A right turn on B83 transported me into another reality. Verdant fields turned to saltbush, peppering sere red soil. Flat coastal plains surged up into rough peaks. I stopped for the night in Quorn, a former railroad town that retains an “Old West” aesthetic. Brisk wind carried the nervous chittering of corellas. Lots of them. I followed the sound to a field near derelict railway buildings. A feathery snowdrift of birds covered the ground. They rose in a raucous cloud, cramming every branch of the bare trees. Maybe they didn’t all fit, or maybe some were indecisive about the roost, because half the group soared over the pitted road to a different tree. After a garrulous pause, they returned.

So went the dance, a winged tide ebbing and surging every few minutes. Hypnotized, I photographed furiously with cold, clumsy fingers. I often envision animal encounters in some remote location, torn from the National Geographic magazines I collected as a kid. Who expects marvels across from a small-town caravan park? Yet this ranked among the most magical moments I experienced in Oz: a thousand parrot bellies tinted gold in the sun’s last rays, swirling like a galaxy in the blue dusk.

REFLECTION: Keep your senses open, including your sense of wonder. Nature can take your breath away anywhere.

Clouds lingered as I headed north the next morning, adding drama to the stark scenery. I pulled over every few miles to take pictures of snags grey and lonesome as tombstones, emus grazing on the plains, or abandoned farmsteads. The most impressive example of the latter was Kanyaka Station. Built in the 1850s, it was among the region’s largest livestock farms, until extreme heat and drought killed thousands of livestock, leading to the site’s abandonment in the 1880s. All that remains now is a maze of roofless stone buildings.

Wandering among them beneath that all-swallowing sky sent prickles along my spine. The inhabitants had tried to fit the wilderness into a woolshed, penned up and sheared for profit. Overstocking, plowing, and grazing on stations like this permanently altered the Flinders Ranges ecosystem. Ironic that humans can impact the ecological functions of an entire planet within decades, but couldn’t maintain a stock farm through a few years of drought. Clearly we haven’t absorbed the sustainability lessons that Kanyaka represents. Will Sydney or Melbourne become similar shells, only steel rather than stone? Who will remain to ponder the ruins?

REFLECTION: Humans are not exempt from natural forces, especially those born of our own short-sighted exploitation. We reap what we sow.

I spent the next day exploring the trails around Rawnsley Bluff, named for a colonial surveyor (or, as some waggishly assert, for the fraudulent credentials he used to secure the job). The steep formation blocked the sunrise, shading the xanthorrea in muted colors. Wallaroos breathed steam into the chilly air, and thornbills sang in the pine trees. Blazes of white paint marked the route up a near-vertical rock slide. I climbed for about a kilometer, contemplating the age of the stone beneath my boots. Geologically, I was ascending from the floor of what used to be an inland sea. At the top, Ikara’s basin opened below me, a biological cauldron that had cooked up some of the first multicellular life forms more than 600 million years ago. Those organisms had eventually evolved into all the animals I’d encountered that morning, including myself.

Rock also records the emergence of humans in this landscape. I saw an outstanding example at Arkaroo Rock, an overhang that shelters 5,000-year-old indigenous paintings. Morning light wakes them gently from the stone, streaks of white and ochre daubed by ancient fingers. What stories animated those minds? Perhaps the creation myth of Ikara, said to be the bodies of two great serpents. Or maybe the shapes represented aspects of the environment: branching strokes could be gum trees or bird tracks. Did they feel the same driving creative energy I do when I write? Homo sapiens might have swapped paint for pixels, but the activity remains unchanged: trying to capture the swirling contents of our primate brains, and leave some imprint of our consciousness that might outlast our bones.

REFLECTION: Despite the supposed “advancement” of our civilization, humans are but a pebble in the strata of geological time, still seeking to articulate our place in the universe.

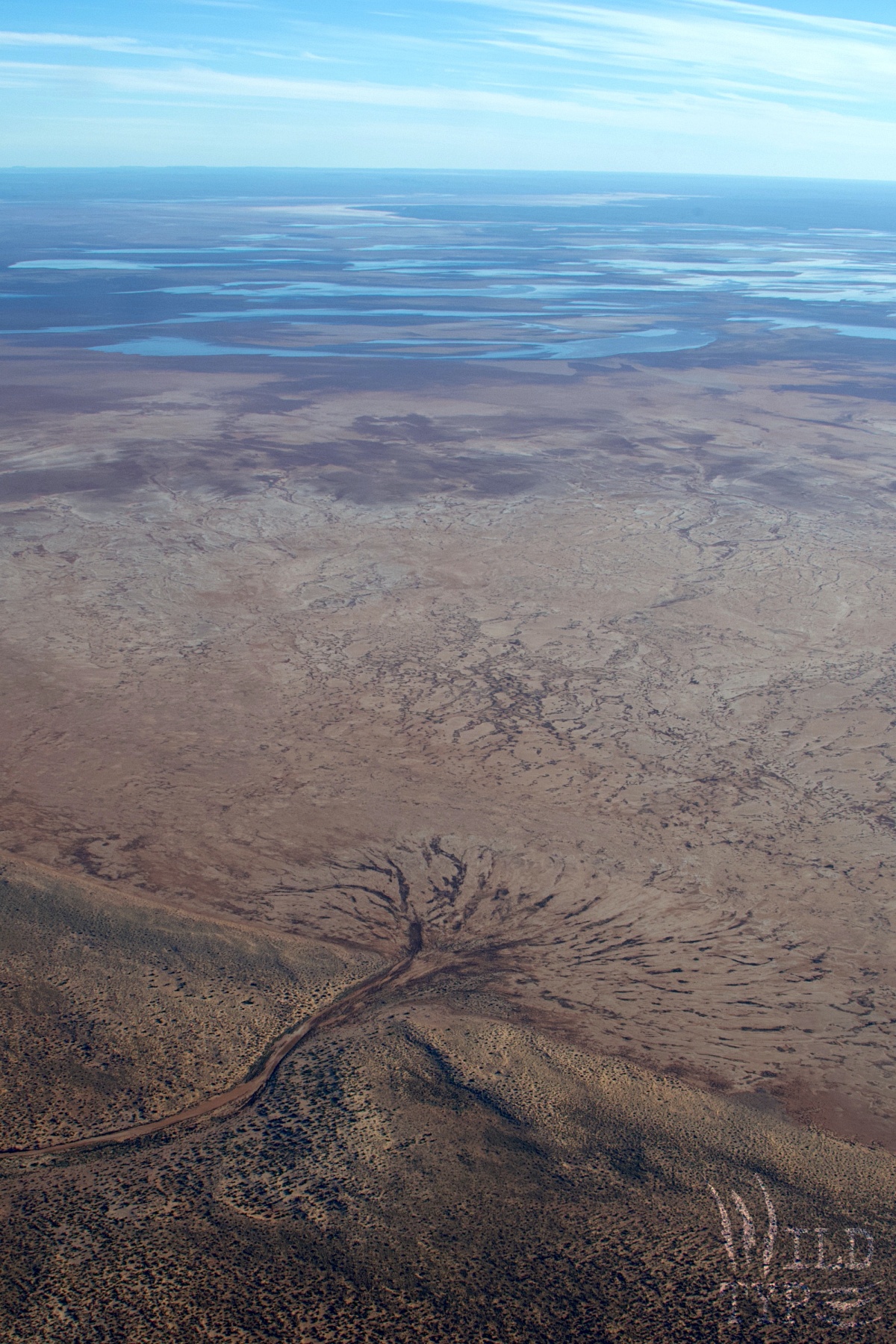

After all that hiking, I rested my legs in a six-seat Cessna for a sightseeing flight. Features that looked impressive enough from the ground revealed their astonishing scale. Artist Hans Haysen described the Flinders Ranges as “the bones of the Earth laid bare”, and the indigenous Adnyamathanha people believed the area’s geology represented Mother Earth’s skeleton. Centuries apart, human imaginations awed at these mountains. Ikara yawned green amid a labyrinth of arid anticlines. Dark alluvial veins etched tree shapes in the dust, memories of water. Kati Thanda/Lake Eyre, partially filled from the record wet season up north, mirrored the sky. Salt streaks mimicked clouds. Flight became a disorienting illusion of hanging upside-down!

Humans had left their marks, too: a bald quadrangle on Ikara’s floor where settlers tried to farm wheat in the 1800s; ruins scattered across the landscape like abandoned shells on a seabed; the gangrenous, smoking wounds of Leigh Creek’s coal mine. But they seemed small scars on the the planet’s vast skin. No artifice could rival the braided formations on Anna Creek Cattle Station, or the puddle mosaic of Lake Torrens shimmering in the afternoon sun. Australia’s harsh majesty left me breathless. Anyone blithely confident in our species’ future on Mars should take such a flight. Such parched, forbidding worlds can’t be easy to survive. When the Cessna kissed the dust beneath Rawnsley Bluff again, I returned to Earth in more ways than one, dazzled and humbled.

REFLECTION: Put yourself in perspective. Things are likely bigger and more complex than you think…and on nature’s stage, many human gripes seem very insignificant indeed.

Outback landscapes seemed like red reflections of my soul. The past three years have been a bushfire, razing me to psychological bedrock. An international move during a pandemic. Lockdowns. Acclimating to life in a strange land. Overcoming a personal cancer scare, then nearly losing my beloved father to the real thing. Nursing my Laddie through surgery for a serious injury. All while pioneering a new position at work. But an Aussie colleague once told me “this land was made for fire.” Growth emerged from the ashes of my old life. Amid the coral reefs, jungles, highlands, and deserts, I rediscovered nature, and myself. It’s been a transformational experience. I’ve loved my time in Australia, and hope that someday I’ll find a path back.

For now, another journey beckons: a new job in a new country. I’ll need all my freshly honed resilience to thrive in a place that rivals even Oz for environmental extremes. Where am I headed, and what will I discover? Stay tuned to find out (it’s a good time to hit that “follow blog” button). I look forward to sharing fresh adventures with you soon!