Science rescued poetry for me.

Verse had charmed me as a child. Dad often read kid-friendly poems aloud; I can still recite The Owl and the Pussycat and How Doth the Little Crocodile. Mom encouraged us to write haiku, limericks, and other forms as part of our homeschool education. My whole family loved Shel Silverstein’s brilliantly zany poems.

The magic faded in my undergraduate creative writing program. Clever rhymes and wordplay decomposed into angst-ridden free verse. If this was “adult” poetry—wallowing in emotion and tortured metaphors—it wasn’t for me. Once I’d satisfied the course requirements, I fled for fiction.

Yet poetry found me again in unexpected places. As my interest in science (another casualty of the English department) reemerged, I discovered lyricism in the non-fiction works of Carl Sagan and Rachel Carson. I had never imagined that disciplines so sharply segregated in academia could make such beautiful symbiotes.

In December 2022, I stumbled across a poem by astronomer Rebecca Elson. With the elegance and economy of a mathematical equation, her words woke the poetic part of my spirit from hibernation. I eagerly obtained a copy of her anthology A Responsibility to Awe, initiating an accidental poetry renaissance in my life. A few months after reading Elson’s book, I encountered the work of Judith Wright, who turned evocative verses about my favorite Australian wildlife. Browsing a used bookstore that November introduced me to Mary Oliver’s soul-stirring nature poems.

All three writers embraced the natural world, themes that resonated more deeply with me than anything in my sophomore syllabus. I’ve even made a few timid attempts at writing my own poems in their tradition. Don’t worry, I’m not going to subject anyone to my doggerel here! Instead, to celebrate National Poetry Month in April, I want to highlight these poets who transformed my appreciation for the craft.

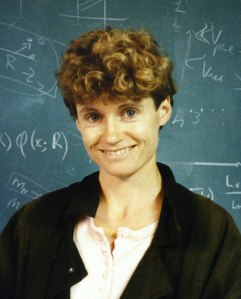

Rebecca Elson

Canadian astronomer and poet Rebecca Elson (1960–1999) grew up close to nature, accompanying her geologist father on field trips. Starry northern skies propelled her curiosity broke Earth’s gravity, and she earned her degree in Astronomy. She intended to study study star clusters for her post-doctoral project, using data from the soon-to-launch Hubble Telescope. When the 1986 Challenger disaster delayed Hubble and halted the U.S. Space Program, Elson found succor at university poets’ gatherings. Creative writing gave her a new lens through which to examine the universe.

The existential themes of poetry and astronomy took on achingly personal dimensions with Elson’s non-Hodgkins lymphoma diagnosis at age 29. Her verses turn tragedy into bittersweet scientific inquiry. In Antidotes to Fear of Death, she reflects on ” The light of all the not yet stars / Drifting like a bright mist, / And all of us, and everything / Already there / But unconstrained by form.” Her illness went into remission in her 30s, and she finally got to work with Hubble imagery, revealing new wonders in the cosmos. After resurgent cancer returned her to that stardust at age 39, her husband and a friend selected some of her poems for the posthumous collection A Responsibility to Awe. Its poignant meditations inspire readers to seek the eternal in the ephemeral.

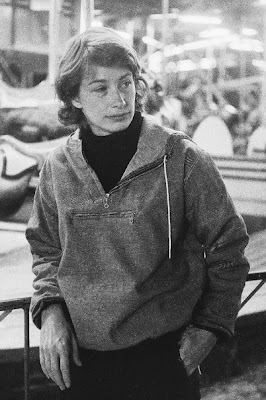

Judith Wright

Australian writer and literary critic Judith Wright (1915-2000) captured a nation’s conflicted soul. An ardent environmentalist and campaigner for Aboriginal rights, she believed that poets should concern themselves with social problems. Wright helped found the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland in the 1960s. She fought to conserve two of the territory’s treasures, K’gari and the Great Barrier Reef, from industrial ravages. Her poem Australia 1970 seethes with rage at environmental destruction: “I praise the scoring drought, the flying dust, / the drying creek, the furious animal, / that they oppose us still; / that we are ruined by the thing we kill.”

Wright attributed this callous treatment of ecosystems to exploitive colonialist attitudes. These themes appear throughout her oeuvre, exploring abuses of both nature and native peoples. She befriended Aboriginal poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal (formerly Kath Walker), and supported her publication of the first poetry book by an Indigenous Australian. Through art and activism, Wright pursued a more equitable future for her country. Her legacy endures in several Australian literary awards that bear her name.

Mary Oliver

Drawn to nature from young age, Mary Oliver (1935–2019) coped with a difficult childhood through writing. In her late teens, she worked as secretary to the sister of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, helping organize the late Millay’s papers. During this time she met photographer Molly Malone Cook, who became her partner of more than 40 years. The couple lived in New England, where solitary walks inspired many of Oliver’s poems. She reportedly hid pencils in trees so she would never be caught without a writing implement.

Oliver’s work chronicles her nature observations in language as spare and clean as a seashell. Her poem The Kingfisher describes how the bird “rises out of the black wave / like a blue flower, in his beak / he carries a silver leaf. I think this is / the prettiest world—so long as you don’t mind / a little dying”. Her collection American Primitive won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize, and the 1992 National Book Award went to her New and Selected Poems.